The question we must ask of any overlooked film left to gather dust in time’s implacable advance is this: “How was this one forgotten?” In the case of Noriaki Yuasa’s The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch, the answer is simple: “Oh. That’s how.” Not that The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch isn’t good, or at least one worth putting eyes on. Yuasa directed the picture three years after working on Gamera, his sophomore effort and the movie he’s best remembered for today; watching an FX-oriented director like him pivot from kaiju to yōkai at the start of his career is fascinating if nothing else.

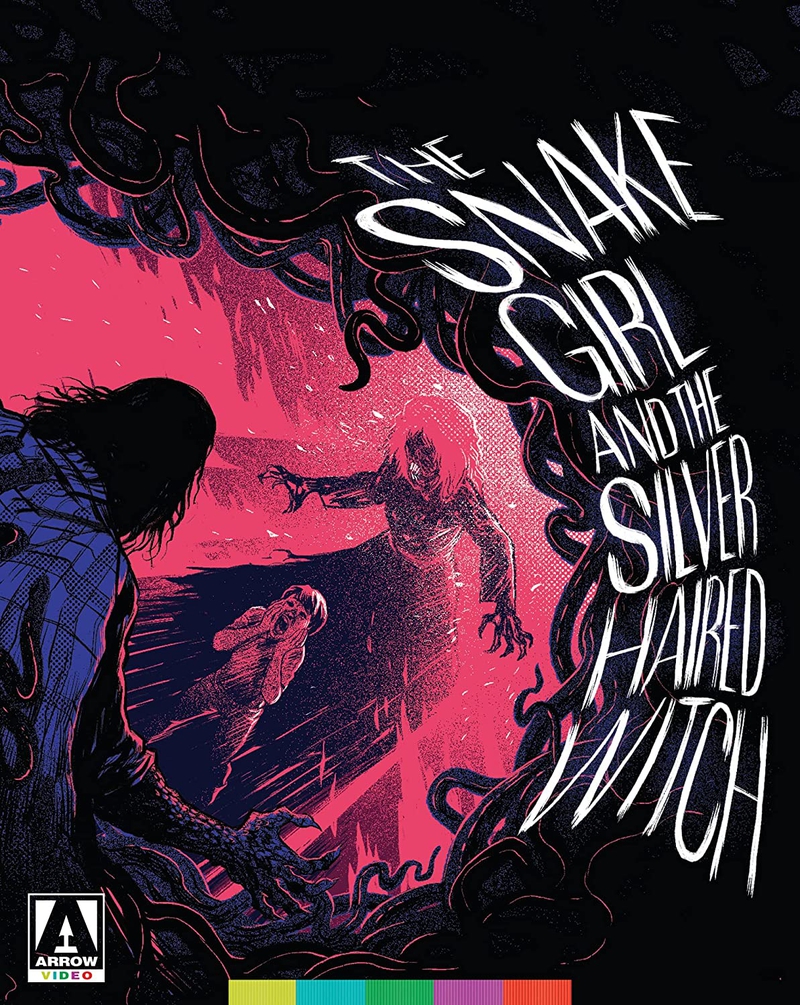

The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch, available on Blu-ray for the first time this December courtesy of the folks at Arrow Video, is certainly more than just fascinating, but part of the fascination lies in where the movie fits in Yuasa’s filmography. The rest lies in the film’s successes and failures outside the context of its director. Take a glance at what Yuasa made after shooting The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch. Here, have a hint: It starts with the word “Gamera.” From 1968 to 1980, Yuasa directed Gamera vs. Guiron, Gamera vs. Jiger, Gamera vs. Zigra, and Gamera, Super Monster, his final film, largely made up of stock footage cannibalized from all the Gamera movies before it. Maybe Yuasa really liked Gamera. Then again, The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch’s modest box office probably didn’t give his Daiei Film bosses much incentive to let him try his hand at anything other than monster blockbusters.

A shame, that. The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch is a compelling curio both within Yuasa’s filmography and without. On paper, the movie sounds like a wild ride, Japanese genre cinema at its wackiest: A nure-onna, a palette-swapped yūrei, a spooky old house littered with peepholes in the walls and ceilings, murder-by-snake, bizarre dream sequences, and comical tonal mismatches. If we’re playing free association games without watching the movie first, then The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch may read like a spiritual sibling to Hausu, but this is incorrect; very little in the annals of any nation’s cinema exists on the same batshit plane as Hausu, and so the standard that film sets is impossible for most others to meet.

It’s more correct to treat The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch as a Scooby-Doo mystery instead. When Sayuri (Yachie Matsui) is whisked away from the orphanage she has called home for her whole life by her birth parents — Goro (Yoshirô Kitahara) and Yuko (Yûko Hamada) — she assumes her life’s about to take a turn for the better. Why would she think otherwise? She’s finally reunited with her parents! Dad! Mom! Sure, it’s a little weird that Yuko calls her “Tamami” to start off, and it’s an odd coincidence that just before Sayuri moves in, the family maid kicks it courtesy of a heart attack, too; her nightmares featuring an apparent nure-onna (“wet woman,” or, for our purposes, “snake girl”) don’t help, either. But at least Sayuri has a room of her own!

Then she meets the real Tamami, the plot thickens, and suddenly the ol’ orphanage doesn’t look too bad after all. At least there, the nuns will ostensibly protect her from being eaten by her half-reptilian “sister,” who isn’t Sayuri’s sister at all, and also treats her like moldering garbage. In Tamami’s defense, she’s relegated to living in the attic like Bart Simpson at the end of “The Thing and I.” There’s a reason to feel at least a little resentful of Sayuri. But of course the resentment is taken way too far, and that’s before Sayuri is stalked by a hideous silver-haired witch, too.

For all The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch’s tantalizingly strange promise, it’s shockingly middle of the road verging on tame. Sayuri, who communicates with Yuasa’s audience through voiceover as much as through spoken dialogue, takes every revelation with surprising and frankly incongruous grace, as if it’s a rite of passage for kids to find out that their amnesiac mother has been stowing away a heretofore unknown sibling in a crawlspace. Her vivid dreams should cause her more alarm than they do, too, though being as the dream sequences comprise the best scenes in the movie, maybe we can let it go that Sayuri takes her increasingly batshit visions in stride. After all, when you’ve had one dream about your new sister turning into a fanged, hideous monster, haven’t you really had them all?

In Sayuri’s dreams, chatter is kept to a minimum. Yuasa lets his imagery do the talking; Tamami shows off her fangs for the audience against transporting and funky backgrounds. Sayuri crosses swords with menacing snakes like a stalwart knight doing battle with dragons. Yuasa might be trying to lull us into a mesmeric state with the hypnotic spirals he uses in every shot for these sequences. The surreality of these beats deliver on The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch’s promise as a horror film and a showcase for a filmmaker drawn to the production specifically by mythology and the chance to expand his talents for storytelling through special effects. It’s the standard mystery plot and whodunit elements that clash with the movie’s aesthetic genre values.

It’s these pieces that make The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch such an oddity rather than the demonstrably odd details. How could a movie where a character rips a toad in half with her bare hands and where the protagonist nearly meets her end in an acid bath bother being so stiflingly normal the rest of the time? It’s a big ask for Yuasa to operate on the level of Hausu, and no one should walk into The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch expecting that (but again, no one should walk into any movie expecting Hausu). But Yuasa hits such hypnagogic peaks when Kimiyuki Hasegawa’s screenplay, based on Kazuo Umezu’s book Hebimusune to Hakuhatsuki, lets him cut loose that it’s hard not to imagine “what if?” Maybe that’s an unfair expectation, too. If Yuasa went bugnuts for the entirety of the film’s duration, it might not be Hebimusune to Hakuhatsuki at all.

Think of The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch not as a near-miss but a near-hit. The triumph of the movie’s practical FX and the collision between its blend of family adventure and theatrical horror is impossible to look away from. There’s nothing like a good puppet show to help horror graduate from merely “creepy” to “scary,” and these scenes are scary in the best way. Letting The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch get under your skin is a delight, just as much as considering the place the film occupies in Japanese horror traditions, as well as Yuasa’s body of work, is instructive. You can learn a lot from a movie that doesn’t quite get there. That’s The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch, a movie of bungled opportunity with plenty to say about the era it was made.

The Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch is available on Blu-ray (for the first time ever!) December 14, 2021. Pre-order your copy now.