I distinctly remember the moment I was first intrigued by the possibilities of AI Art. On December 13th, 2021 I was scrolling through Twitter and breaking up the endless parade of apocalyptic news stories, vicious wisecracks and obscure movie trivia fighting for space on my feed was a puzzling and bizarre comic-grotesquerie “Elon Musk Dying in Space,” created by one @wagface.

"Elon Musk Dying in Space" pic.twitter.com/G2ta7jCxps

— Wagface (@Wagface) December 13, 2021

No malice towards Mr. Musk, but one thing I love about Twitter is how the rich and poor, the powerful and anonymous are all trapped together in the same canvas sack, and this was a striking example of an anonymous online wise-guy turning the tools of cutting edge technology against one of the world’s most pre-eminent technologists. I was also totally baffled, “What, exactly, am I looking at?” The image’s melted plastic, smeared pixel future-primitive aesthetic couldn’t’ve been more appropriate towards the subject at hand, but how was this nightmare created and what else is it capable of creating? These questions would plunge me into a new rabbit hole (I tend to fall into them fairly frequently) that, as of this writing, I have not managed to pull myself out of.

I also tend to drag others down with me and I have a half-dozen friends with whom I regularly text the most promising, successful and/or horrifying, appalling experiments as we navigate the different apps (from Starryai to Midjourney, Craiyon to Dall-e 2) and practice our, ahem, “prompt-craft.” Strangely enough, I can see each person’s aesthetic in their work, from one friend’s sci-fi-decadence to another’s satirical-grotesque, no matter the generator.

Whichever app you use, the “creation” process involves typing plain-English text-based requests into a little window and then waiting a minute or so for fully rendered, high-resolution images to pop out, images that never existed before and whose origins are deeply mysterious. Seven months into this new obsession and I’m still agog every time a really interesting image comes through. It feels like sorcery or science fiction. I know that it’s impossible for something to come from nothing (or at least it used to be) but converting text to image (without the addition of a human being, art supplies and time) seems like the next best thing.

Digression: It’s also an open question as to who is training who, as I consider how my prompt-style has evolved from something simple like “Frankenstein’s Cat” or “Werewolf Cop” to the considerably more elaborate “16mm filmstill of two large alligators exploring an abandoned luxury car dealer with high tech fixtures, two inches of water on the floor, lit by small trash fires” or even “Clipped photos from ‘80s fashion magazine pictorials assembled into a collage depicting a crowded futuristic indoor arena where the colored-toga-clad audience cheers on people wearing goalie masks and white bodysuits float upwards towards a giant red crystal while lasers flash around them.”

The unsettling mystery of image creation might go a long way to explaining why the format lends itself so well to horror; after all, these images are coming from BEYOND. In fact, I remember two times the AI art process itself frightened me.

The first was when I went through a period of forgoing concrete descriptions of imagery in lieu of evocative quotes from a variety of sources. It was an experiment to let the AI creatively interpret more ambiguous prompts. On a whim, I entered “Yog-Sothoth Ngh'Haa Ygnaiith Fthagn” (a line in H.P. Lovercraft’s mystical ‘Aklo’ language as found in Alan Moore’s Neonomicon) into Starryai, hit “generate” and was rewarded with this eldritch image.

I was thrilled and horrified to see a result that looked like it came straight from the Mountains of Madness. How had it possibly managed to understand Aklo?!? Were humans meant to gaze their eyes on these sorts of inexplicable horrors?

I went on tempting fate until I had about two dozen similar images, all generated by Lovecraft quotes, leaving the question of which alternate dimension’s database of occult imagery the app was searching through for another time. After completing the series, I went on to conjure up a half-dozen paintings based on the extant fragments of the King in Yellow play (according to the novel by Robert Chambers, its one performance drove its audience insane) but an apocalyptic wave of contagious madness never quite ensued. Give it time, I guess.

The second time I needed to pause and reflect was during my short flirtation with the Midjourney app (I started with Starryai, did a few rounds with Dalle-mini and then lucked into an invitation to my current AI art generator of choice - Dalle-2.) What was is about Midjourney that I found so disturbing? Some of it was the imagery that came out, no doubt - Rob Sheridan is one especially talented artist creating unforgettable monstrosities with it - but the real horror for me was Satre’s Hell of other people.

The interface for Midjourney wasn’t a tidy app sitting on your own personal device, it was a semi-public discord server where one user after another threw their prompts to the wind. It rained down (or rather scrolled up) like confetti, and reading them was an all-too revealing x-ray (or perhaps colonoscopy) of the darkest imaginations found online. Hundreds of horrifying prompts like “satanic angel eating the still-beating heart of a crucified priest” or “the extinction of hope from the eyes of a burning dove” racing each other into the still-forming consciousness of a nascent artificial intelligence. If these prompts are educating it (and I don’t consider my own experiments much better), then what is this baby going to be like when it grows up?

(Above: artist and filmmaker Graham Reznick's AI art, created using Midjourney)

Meanwhile on Dalle-2, the AI Art Generator which, to my eye, creates the most accomplished-looking images, the prompts need to stay PG (its engineers seem to fear the consequences of all-too-realistic depictions of the worst the general public can imagine. It also avoids all political figures and even perfectly innocent words that might be inappropriate in certain contexts.) Nonetheless, the photo-realism of the human characters it creates has made it out of the uncanny valley and into the mountain range beyond. Some of its faux-paintings do a pretty good job of tricking the eye as well.

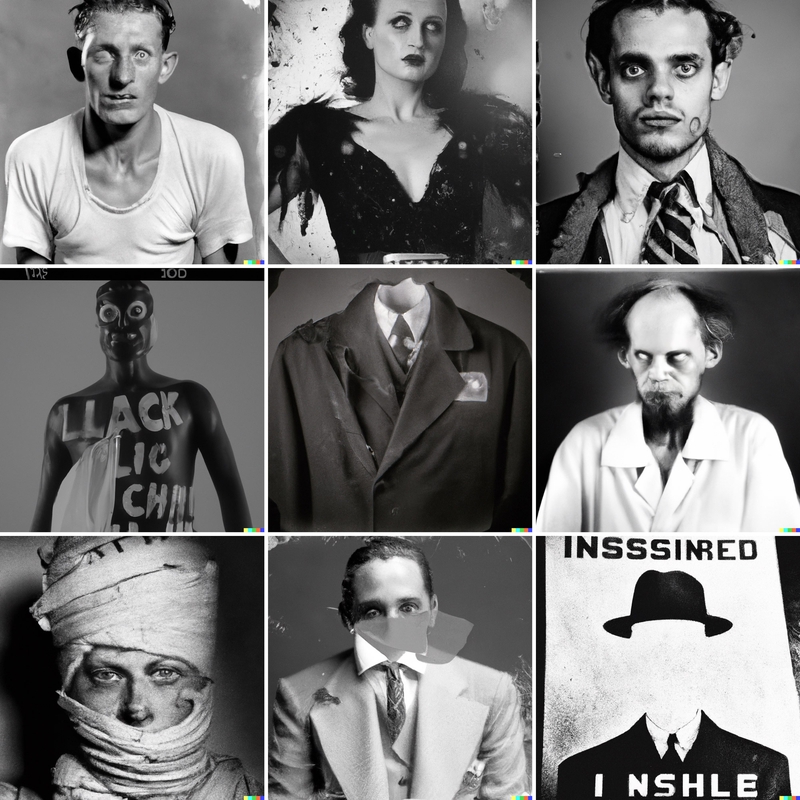

I’ve been really excited by the images I’ve gotten out of it recently, from a series of mugshots of Universal Monsters to 16mm film stills of a post-human future to portraits of forgotten supervillains. But the question remains - who is making these images? Me? The programmer of the apps? The 1000s of artists/photographers whose work, without consultation let alone compensation, has been chewed up, digested and spit out as part of the process?

(Above: the author's "Universal Monsters Mugshots" series, created using Dalle-2)

I don’t know exactly, and I don’t really think there’s a definitive answer. After I enter my prompt I wait in absolute ignorance of what’s going to emerge but once it does, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit to feeling a sort of after-the-fact authorship. Still, I can imagine the objections to claiming to be the artist who made this stuff and I can argue them both ways.

“You didn’t make this, the app’s designers did.” Maybe, but photographers don’t co-sign copyright of their images to the camera’s designers. I think AI art generators are a tool unlike most any other, but I still think they’re a tool. To my mind, it’s not an exaggeration to say it’s as revolutionary as earlier breakthroughs I’ve witnessed firsthand, from MiniDV to Final Cut to After Effects.

“Typing in a plain-English description isn’t the same as creating an image” Maybe, but it happens to be the way filmmakers typically interact with their human collaborators (which might go a long way to explaining why so many directors I know have fallen into the AI rabbit hole). Telling a cinematographer to light a room “dark and eerie” and letting them translate that to artfully deployed lighting gear and camera settings is pretty standard practice, as is telling the warddrobe designer that a character should wear something as vague as ‘fashionable that stands out from the crowd” and letting them find options from boutiques and brands you’ve never heard of. That feels an awful lot like how we talk to AI programs.

In fact, that very style of collaboration is the basis of a long-standing debate between Stan Lee and Steve Ditko in reference to the authorship of Spider-Man. To simplify (and, for now, ignoring Jack Kirby’s skin in the game) Stan once said “I had always thought I was [the creator] because I’m the guy who said, ‘I have an idea for a strip called Spider-Man.”

Steve Ditko served up this rebuttal:

Steve’s argument for being a full-partner in what makes that character distinctive is pretty powerful, and proponents of the auteur theory might ask themselves if A Clockwork Orange is just a Kubrick movie or could be seen as a Malcolm McDowell one (or perhaps, an Anthony Burgess, or Wendy Carlos film for that matter.)

The fine art world is filled with artists who take full credit for work they make in conjunction with a larger team, from the artisans who fabricate Jeff Koons’ collosal metallic balloon animals or the factory workers who sculpted the urinal that Duchamp would name “Fountain” and sign R. Mutt (to complicate things, there’s allegations that Duchamp stole the idea from Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.) Even renaissance artists like Davinci had countless assistants who filled in the backgrounds for them.

The Dall-e app calls the work a collaboration between human and AI creators and at the end of the day that’s probably the fairest. For an example of a work created by two humans, one highly skilled in a technical process, the other using ‘plain English,’ check this video where Angelo Badalamenti explains how he wrote Laura Palmer’s theme with David Lynch.

And yeah, I feel for the legions of artists whose work the AI draws from, but I also find the process of AI ingesting millions of images before “creating” its own similar to the human experience of being audience before author, and being unable to escape our influences. Watch Kirby Ferguson’s great video series “Everything is a Remix” for a masterclass on, as Jonathan Lethem calls it in his essay on the subject (itself entirely constructed from quotes of pre-existing works) ‘The Ecstasy of Influence.”

We’re in what I imagine is uncharted legal territory if/when AI art makes imitating the style of living artists and undercutting their ability to sell their art competitively and, while I’m excited about AI’s ability to allow more and more people to exercise their creativity in new ways, this prospect does make me wary of what sort of Pandora's Box is being unleashed here. The debate about these issues and their possible ramifications is exploding, and I don't claim to have the answers. For the meantime, some of this controversy may be a moot point as AI art is, apparently, not copyrightable.

It does feels like “prompt-craft” is an embarrassingly low-effort way to create art but in my experience the best results come from people who already have spent real time mastering different visual arts, people who have the patience to see something with potential and nudge it along through countless iterations to reach its potential. A process that sounds dangerously close to art-making. 90 percent of AI Art probably sucks (mine especially) but I think you could probably say the same for any artform.

In the short time I’ve been exploring the tech I’ve seen it evolve from completely baffling, accidentally surreal approximations of illustrations to photo-real portraits of imaginary characters. People (myself included) have been doing experiments with AI-based slideshows, some to great effect, but one week ago I saw my first AI-generated film complete with AI-generated voices and I had to once again, adjust my understanding of what’s possible.

Another Ai filmmaking experiment.

— Jon Finger (@mrjonfinger) July 27, 2022

Every pixel you see and voice you hear is generated by AI.

Apps:

Images: @midjourney

Voices: altered ai

Faces motion: Reface app

Camera movement: PopPic app pic.twitter.com/5gboySN4Rg

Does this technology have the potential to create havoc, putting artists out of work, filling the world with ugly, half-assed fake art while further eroding the public’s faith in photographic evidence in a world all too filled with misinformation and too starved for real art? Sure. But it also opens us up to one where more people are able to translate their ideas into artwork in multiple (virtual) mediums, which sounds like good news to me. Which will it be? Probably both but, in the meantime, I can’t seem to stop typing new prompts into the window and hitting ‘generate.’