When the pandemic hit, my friends and I stocked up on snacks and started weekly zoom movie nights, trying to find some joy and stillness in the chaos. We had a chat we have a lot. We always question whether horror fans have a favorite subgenre. Horror is an umbrella term, that lends itself to the largest scope of genre intersections. Horror comedy, zombie films, supernatural, experimental, anything you need.

Mine happens to be cannibal films.

At 14 years old, I was scrolling through YouTube and a related video came up. “THE MOST CONTROVERSIAL MOVIE EVER MADE” and an image of red, collective violence caught my eye. I didn’t know what I was letting myself in for, but it became a moment that would shape my mind more than I realize even now.

I’ve long been fascinated with humanity’s propensity for violence. Is it inherent? An insatiable need to consolidate power through instilling fear? Is it the thing we connect to the most? Or is it drummed into us as children? Are we merely products of governments and institutions that have been built on blood-soaked soil?

My fascination with this question, a lifelong focus, takes me to all corners of genocidal, military, and dictatorial history. Libya, Germany, the former USSR, Rwanda, Armenia, America, China. There’s a long history of systematic and individual violence that permeates all identity markers. Any markers are used as the regime or perpetrator sees fit. They are fluid and malleable to suit whoever is inflicting the violence.

If you look at any sort of genocidal or regime history, there’s a deep sense of overwhelming heaviness. Even if the perpetrator or dictator is brought to justice in some way (The assignation of Gaddafi in Libya, or Mussolini being strung up in the streets in Italy, were two historic overthrows of extreme dictatorships), there’s still an immense amount of pain, suffering, and generational trauma that will leave a print on that community for decades to come.

It could be said that there is no psychological justice. Violence inflicted on you stays with you. There is no real comeuppance for the victims and no amount of release or removing that pain, even if conventional justice is served. This opens up all types of questions about revenge, retribution, and what righting unimaginable violence entails.

This is what I love about cannibal films.

No other films so viscerally shape the ramifications of culture clashes that really shouldn’t have happened in the first place. There’s something deeply satisfying in the subversions and layers that are cleverly put into narratives. Even if the director didn’t make these layers a primary intention, there’s still lots to explore.

There’s a nod back to colonial history. The pseudoscientific classification of “savages” all over the world that had “no culture” (although Britain, France and Belgium, among other empires, took much of the literature and artifacts and burnt the most sophisticated stuff, because it really was that good). Most cannibal films are set with this traditional background. They take western groups of anthropologists, student activists or psychologists, and thrust them into the jungle, where they become victims of their ignorance.

But I can’t get away from this beautiful inversion that happens which keeps me coming back. There is a duality when we talk about the “other” or the “savage.” They are objectified as two things. “Savage” and “uncultured” breed a false sense of inferiority. On the flip side, they're still fashioned as a symbol of fear – so they must be something to be taken seriously.

Cannibal films don’t shy away from this at all. They turn it on its head in a way I’ve seen very few subgenres of film do.

Western ideology, just talking in terms of historically forcing colonizing empires’ cultures on other lands through violence and genocide, puts our psyche, when we watch these films, into the assumption that westerners on screen are always in a place of power. Whether we like it or not, we know nothing is going to really challenge these main characters, and not much will change them permanently.

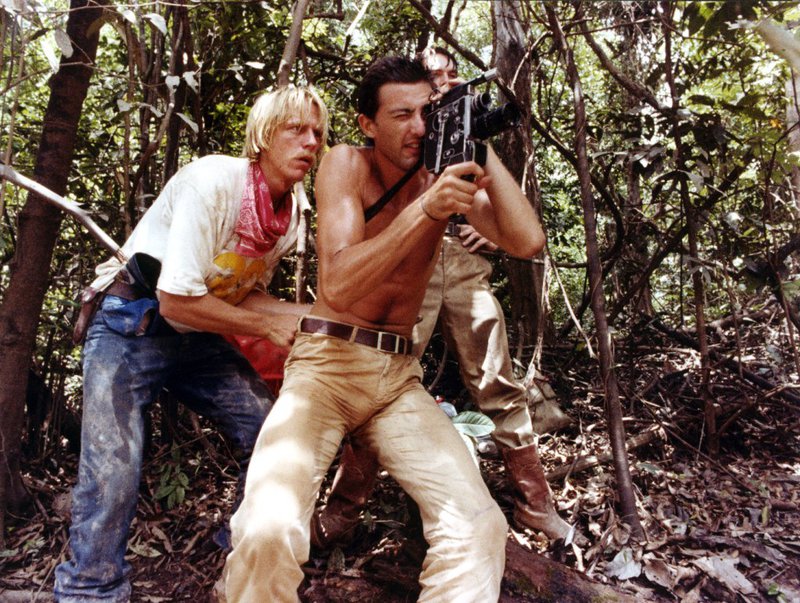

Ruggero Deodato's Cannibal Holocaust, probably the most famous cannibal film, reaches into the idea of power and resistance. A group of American filmmakers goes to the Amazon to make a documentary about indigenous cannibal tribes (Americans are always doing the most in films like this. You want to go into a jungle, that you’re not familiar with, and make a documentary, not about the animals… But ABOUT CANNIBAL TRIBES?). The Americans are intrigued by the tribes they meet. There’s a conflict between the ethics of journalism, artistic liberty and human empathy. Ethics are thrown to the wind when they burn down the village of the peaceful tribe, just to make for a good scene in their documentary. Leaving carnage in their wake, they come across another tribe not as friendly. Audacious, satisfying revenge occurs and the Americans are brutalized and eaten.

There’s something very clear about the links between fear and intrigue in these films. There’s a deep sense of frustration in Cannibal Holocaust. You’ve just seen human carnage but you feel it justified as the Americans terrorize a peaceful tribe. In Umberto Lenzi’s Cannibal Ferox, you’re watching them cook a tortoise in its own shell. In the Wrong Turn films, you’re watching mutants hack your friends to pieces for their second breakfast. But you still venture deeper, because the fear and the excitement that come with terror are palpable.

In the context of cannibalism, and the historical and cultural significances of it (even spiritually – some historical tribes believed if you ate the meat of your slain enemies, you would inherit their power), there’s a deep sense of cyclical chaos, just as there was when Britain was at the peak of its colonial empire. As much as Britain created such disdain through racial and cultural systems for anyone it deemed other, it did it for various reasons – but an economical need for slavery, and for dragging valuable resources from other countries, was the main one. These systems sought to demonize and dehumanize the other, so it was easier to exploit them or exterminate them. But it was a need. For what would the British Empire be without its colonization of swathes of the world? What would any dictator be without its eradicating of the pesky “other” that it had pushed all of their country’s problems on?

This hypocrisy and wheel of manufactured violence roll through every cannibal film. The westerners are shocked, appalled, and incredibly terrified… But the cameras? They’re still a-rolling.

But that’s not to say that cannibal films only stop at commenting on our propensity for violence. Wrong Turn comments on the effects of nuclear waste and environmental disaster. (It takes them three films to explain this, but when they do it, it works. The design on the baby at the end of Wrong Turn 3 is stellar, as well.) American passers-by are left to deal with the consequences of generations of families that are born under contaminated water and soil. Invasion of the Flesh Hunters could be seen as Antonio Margheriti’s ode to the violence of Vietnam in a different genre than his usual war films.

Refn’s The Neon Demon, one of my faves, uses cannibalism to symbolize the dangers of aspiring to a perfect sense of self. Set against the backdrop of the fashion industry, it’s a perfect allegory for the sacrifices and destruction of trying to keep up with the next trend, including the mass proportion of eating disorders in the industry. As the film plays out, even when there’s some sort of accomplishment through eating, it is rejected because you can’t fake a real, tranquil, and comfortable sense of self. You just end up eating yourself and maybe… throwing yourself back up.

Raw, from Julia Ducournau, delves into a similar position, using cannibalism as a consequence of trying to fit against the toxic environment of sorority hazings. When the vegetarian protagonist is forced to eat meat as one of her hazes, a rash develops over her body which then translates into an insatiable desire to eat. It almost serves as a manifestation of the way trauma physically embeds itself in your body. The mind moves on, but the body sinks into it and is consumed by it.

Eli Roth’s The Green inferno points a satirical finger at the performativity of student activism and questions whether it’s done for the cause, or for the publicity. It puts the cast through their paces and dares to ask the questions, “What are you doing here, invading? Do you really know what’s best for these people? How far are you willing to go and what will you endure for your activism?”

Whatever way you interpret a cannibal film, there is a deep conflict of self, morals and the push and pull of control. There’s spiritual significance and there is something about watching people eat other people that makes you think about your own mortality. Or all the other ways we’re tokenized and put through the societal meat-grinder in the real world. Cannibal films reach deep into places that we try to hide – the places that put us side by side with anyone who’s done anything to elicit infamy, because we’re all humans, after all. It pulls at the strings of misunderstandings, cultural biases and different attitudes towards life, death and decay.

It’s a film genre that few wade into to create, but I think it needs a new resurgence, as the latest offerings have given us through a new wave of filmmakers. As a subgenre, by its very existence, it’s a test in pushing your limits, smashing convention, and thinking about the human condition in the throngs of terror and gore-filled intrigue.