“Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay / To mould me man?” ― John Milton, Paradise Lost, 1667

The unholy abomination of bringing the dead back to life signaled the domineering presence of science and the destruction of faith during the 19th century. In Mary Shelley’s solace (and raging heart), she gave life to the “mad scientist” and his “creature”; man as monster and the humanity of his abomination; an electrifying theatre of the imagination that set the stage for horror, science fiction, and cinematic history. This classic piece of literature defined our fears through a mournful creature ― the Adam of Victor Frankenstein’s labors ― and became the perfect allegory of its time.

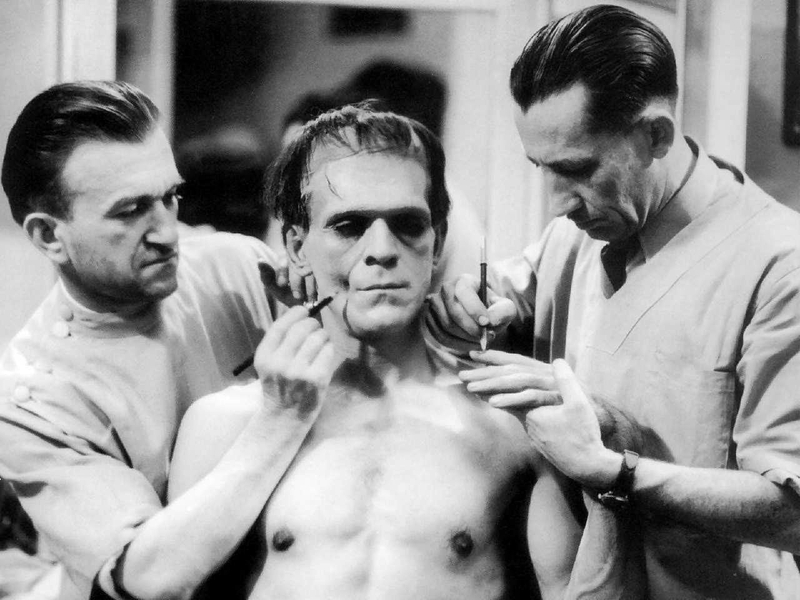

Over two hundred years since the publication of Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), no version of her creature has been more iconic than in James Whale’s (loose) 1931 adaptation. Through Boris Karloff’s portrayal, the imagery has become so potent that, from an early age, we have often assumed that the lumbering presence is Frankenstein and has fed into part of the mythology. When looking at makeup artist Jack Pierce ― much like the source material ― “Frankenstein’s Monster” overshadowed its creator.

From Shelley’s Gothic romanticism, by way of German Expressionism and the birth of Universal horror, the Monster was about to become more iconic than ever before. Immigrant filmmakers forged the early days of Hollywood and Pierce was no different; born as Janus Piccuola in Greece, 1889, he emigrated to the United States with his family as a teenager and soon began a semi-pro career as a baseball player. Too short to make it as a pro he worked as an actor in silent films where, after realizing he would be guaranteed more regular work, he utilized makeup to play more characters. He looked up to and found inspiration in the likes of Jack Dawn and Lon Chaney. After Chaney dropped out of The Man Who Laughs (1928), producer Carl Laemmle hired Pierce to work closely with German actor, Conrad Veidt (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920). The result was creating one of the most influential makeup designs in cinema history, most notably a huge inspiration for Batman’s arch-nemesis, the Joker.

As with most of his earliest work and despite the thrilling plaudits on the release of the films he was involved with, Pierce remained uncredited and, therefore, often overlooked. Although he was respected professionally at Universal, he came with a reputation. Other makeup artists, including Dawn ― who later worked on The Wizard of Oz (1939) ― were embedded in the industry and supplied with a factory of co-workers, while Pierce headed a much smaller department at, what was considered at the time, a second rate studio. It would also seem that after Chaney’s death in 1930, the weight of his reputation would hang over Pierce, becoming almost a gatekeeper of what he had learned first-hand from the “Man of a Thousand Faces”.

Pierce arrived at Frankenstein via the problems he faced with Bela Lugosi during production on Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) in 1930. The (vain) Hungarian actor refused any heavy appliances as the infamous Count and went on to infuriate the makeup artist all the more during a subsequent Frankenstein screen test. With Pierce’s patience pushed to the limit, Boris Karloff ― not known for his vanity ― was more than eager to take on the role, and an immediate bond between the two men was forged. Anxious about the process due to his previous experiences with Lugosi, the more authoritarian Pierce now had the creative control he desired over an actor; Karloff now at the mercy of his own mad scientist.

Due to Shelley’s sketchy descriptions of Frankenstein’s creation, Pierce’s design (with Karloff’s input) was practically unfiltered ― a flat-topped lobotomy dressed in horrendous scars ― his consultation mainly in medical books as he worked out the nuts and bolts of his creation. However, there was also an ego to outdo what had already been done, driven by the processes he had acquired observing and working alongside Chaney. It was no secret that Pierce’s process ― as with most other makeup artists of the period ― used somewhat “torturous” methods. Before lighter and more forgiving latex materials, glues would burn, and applications flaked and fell into the eyes of performers. The story of Frankenstein captures what a being will feel as he exists in a painful skin, and Karloff experienced just that; scarred for life, much like his eponymous character. But, despite the pains (and injuries) the actor inflicted, there was a genuine rapport and friendship between the two men ― crucial to the birth of such an iconic Monster ― Pierce and Karloff continuing to work together on The Old Dark House (1932), The Mummy (1932), and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), to name a few.

The ordeal of being in “the chair” wasn’t so much shortened but improved on slightly as Pierce refined the process with his “plastics” when he and Karloff worked together on Son of Frankenstein (1939) towards the end of the same decade. Yet, his “slight improvements” were not enough to move with the times. Film processes and technologies were changing, and his refusal to ditch his “appendages” and work more towards individual appliances didn’t help as the studios reduced costs to increase profit. A true artist, Pierce had paved his own way within the industry, escaping the operatic shadow of Chaney but, once Universal Studios merged with International Pictures in 1945, Pierce found himself replaced by Bud Westmore. Westmore would later become the head of Universal’s makeup department during the production of another iconic Monster in Jack Arnold’s Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954). Westmore was a strong advocate for foam latex and using masks for creature designs; a method Pierce failed to incorporate, which impacted his career. Falling into obscurity with little to show other than a golden handshake for loyalty to his studio, it seemed the Hollywood way for such patron saints and pioneers to be “dismissed” and, ultimately forgotten.

Confined to television and B movies throughout the ’50s, Pierce watched as the face of horror changed. Hammer Productions put their own stamp on Shelley’s monstrous legacy with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and, before long, the Monster fell into mashups and parody ― Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), The Munsters (1964-1966) ― a desensitized nation reeling in real post-war horrors of dead presidents and conflict at home and overseas. As a veteran and pioneer of the industry ― [re]defining the vampire, werewolf, and other Universal monstrosities ― it is sad to think of Jack Pierce living out his final years forgotten and in near poverty during the ’60s. When he finally passed away on July 19th, 1968 ― just a few months before Romero reinvented the genre with Night of the Living Dead ― only a handful of people attended his funeral.

As a monster parable, the story of Frankenstein has managed to endure so long because of what it says about humanity. Through Pierce’s makeup, Karloff managed to convey the solitude and pain inherent in Shelley’s work. Not just the pain of the Monster but also, in light of the inter-war period, an entire generation of outcasts via an immigrant nation. Whale’s film ― a deeply personal one as a homosexual ― was less the romanticized vision that Shelley portrayed and more of a modernist outlook ― an observation of social anxieties; rejection, and abandonment ― while maintaining the core theme of “gods and monsters.”

In terms of makeup effects, there is a natural legacy from Chaney to Pierce, Smith to Savini, Baker, and Bottin; most of them having championed this maestro as a crucial influence on their work. Having carried over from what had been used on stage, Pierce’s skill was not only in how he adapted the materials at hand to create such iconic monsters; but also how, under the unforgiving eye of the camera, he would blend his effects into a perfect cinematic illusion. Pierce was Dr. Frankenstein. He was the monster maker and mythmaker. Playing God in a lab coat, he molded, revived, and stitched together his version of the Monster during Hollywood’s twilight hours… a true “victor” of monster makeup.

Click below to stream Frankenstein today: