There is vulnerability and emotional magnetism in the intimacy between two women – the common urge to play the voyeur and be connected with someone who shares the same anatomy. Scoop her breast and it’s as if her moan is coming from within you. There is power in sexual freedom; there is power in killing men.

Horror films produce a physical reaction, whether it is from a masked killer slashing someone’s throat or a couple having sex in a secluded cabin. It is that same shock and rushing of the blood that seduces serial killers who have a sexual addiction strangling their logic and saturating them with a craving to kill. Think Jeffrey Dahmer, Rodney Alcala and Ted Bundy, men who raped and murdered for sexual satisfaction. Men whose egos were greater than the society they felt rejected from. The machoistic component of power and control dominates male murderers and rapists as history has shown and psychologists have proven time and time again. Female serial killers, on the other hand, murder for revenge or money. Women have killed their abusive husbands, boyfriends or strangers, whether in self-defense or as a last resort to escape domestic violence. Women murder their attackers before death becomes them. Monster is based on the true story of serial killer Aileen Wuornos, who murdered men and fell in love with a woman. Since childhood she had been abused by men in her family and the customers who requested her sex work services.

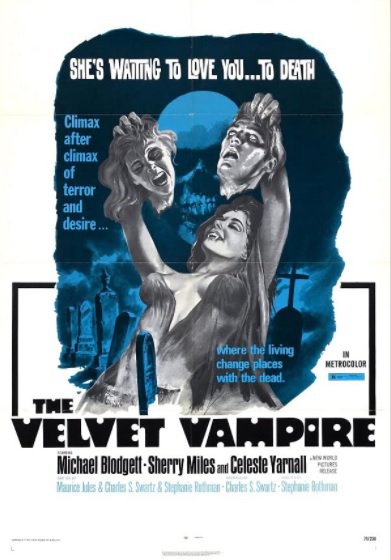

1971's The Velvet Vampire claws into the familiar story of bloodthirsty creatures who crave intimate encounters before they sink their teeth into their victim’s neck. Seduction is a secret weapon they manifest to tame the victims before sucking their blood. It is among the 1970s' horror films with female protagonists who were part of girl gangs, vampire clans and the occasional coven where women dominated. They were sexually charged beings with a characteristic previously unacceptable in both female roles in movies and society, but the late ‘60s and ‘70s brought some change. Horror cinema began to demonstrate women’s capacity for violence in the form of mythical incarnations, such as vampires, witches and monsters.

Although Hammer films like The Vampire Lovers and Countess Dracula gave the vampire throne to women who were thirsty not only for blood, but for sex, a female director hadn’t yet done so. In the last 50 years since its release, The Velvet Vampire has reigned as a cult classic for its avant-garde storyline, surreal scenes and direction by Stephanie Rothman (director of The Student Nurses and former assistant to Roger Corman). Rothman proved that women could write, direct and star as the hunters instead of the prey, form relationships with other women, and experiment with fatal sex with men. As the 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of feminism, women where no longer the victims but the vixens in horror cinema.

Rothman dabs surrealism into scenes like crimson wine in a goblet that seethes through the mouth and alters the vision. Intimate moments are not shocking but romantic, carrying the plot along and showcasing the creature’s plead for the human touch, for warmth and care – sentiments distant to vampires who are cold creatures on the hunt. Details like the rouge nightgown that peaks down to reveal a triangle of Diane’s pale breasts and her dark hair brand her as different from the blondes and tanned people in the nearest city.

Celeste Yarnall plays Diane, a vampire living in the desert where the sun doesn’t threaten her existence. In the opening scene Diane is attacked by a motorcyclist who nearly rapes her. She doesn’t fight, but with a quick bite and a stab kills him. The hunter has become the prey of the lady in red. Diane visits a gallery where she meets the couple Lee (played by Michael Blodgett) and Susan (Sherry Miles) and invites them to her secluded desert home. At the house, Susan dislikes the beef tartare as much as she dislikes the enchantment Diane has on Lee over dinner.

Diane talks about her dune buggy with Lee. Gradual manipulation and powerful control take over with double entendre in her slow voice: “Once it warms up it really comes alive, then you have to watch out. It’s hard to control,” she smiles. “Up and down, in and out – of the dunes,” she adds as if to clear herself from any misunderstanding. “Diane, I think I’d like to drive your buggy,” Lee declares. That night, the vampire bites a mechanic who was working on her buggy inside her garage as she prepares to feast on the couple.

In the bedroom Lee begins to sexually arouse Susan in order to calm her down after she heard a man’s scream, the victim of a bite. Diane attentively watches them through a mirror as the couple kiss, their hands roaming and their bodies twitching. During this scene, the camera is focused on Susan’s upper body and Lee is outside the shot. Diane is entertained and leans forward as Susan reaches an orgasm with Lee’s unseen oral activity, but she refuses to do the same for him.

Susan will not sexually please her husband Lee, and she remains a stranger when he and Diane are talking or exploring the ghost town the following day. She is jealous of Diane, unable to process the same seduction and attention from Lee despite being his wife. Susan eventually admires the vixen’s skills of maintaining his attraction. It’s almost as if Susan enjoys getting rid of her husband so she can have time to herself and sunbathe. Diane does a favor for Susan who wants freedom from her man after he's proven to be disrespectful and untrustworthy. The relationship between the two women strengthens, especially after Diane sucks the snake venom from Susan’s leg after being attacked.

During their stay, the married couple experience similar dreams. It is during these scenes that surrealism overtakes the imagery. A bed is a nest of white sheets where the nude couple mates at the center of sand waves. The breeze brings Diane with a sheer crimson gown as she steps out from a mirror and interrupts the couple. She seduces them both with her bewitching look, tenderness and caressing hands. The milky scenery mirrors the tag line on the theatrical movie poster of The Velvet Vampire: “She’s waiting to love you... to death.” The female killer wants to seduce men, but also women who understand her. She kills men for pleasure and strength, proving she is capable of it just as male serial killers and vampires have done in the past.

During one of the hot desert nights Susan discovers Lee having sex with Diane, who looks back at her, aware of her voyeurism. Their roles have switched since Susan is now on the outside looking in, a simple third wheel that doesn’t fit in with the pair. Diane tempts her with a magnetic look. Susan remains silent and unaffected, and for a second it seems as if she wants to be a part of it and join them in order to be close to Diane. This interaction is a growing glimpse of the relationships of women in cinema. Instead of competing over a man or shaming one another, Diane and Susan don’t fight as viewers would expect women to do. When Diane takes them to the cemetery where her husband Victor is buried, Susan empathizes and comforts her. Lee suspects Diane’s evil intentions, so he searches for his wife so they can escape. Diane and Susan, however, are having a conversation that highlights the bond between the two.

“Susan, have you ever noticed how men envy us?” asks Diane when nobody else but them are around. “Envy us how?” asks Susan, and Diane answers, “The pleasure we have, that only we can have. We can’t help it. It’s just our nature, the way we are and in their secret hearts they hate us for it because they can never know what it’s like.” In fact, men may never know the problems, the pleasures, the pains and the emotions that set women apart from men's machoism and lack of sentimental reasoning. This is what makes Diane so different from male serial killers who butcher for their own pleasure without thinking about others, while Diane kills for revenge and finds a sentimental love affair with another woman in the process. After Susan refuses to leave the desert despite Lee’s warnings, he assumes she wants to stay because she wants to be near Diane. “Well, maybe I do,” Susan proclaims. “How does that make you feel?” Susan has developed an admiration for the rumored vampire who recognizes her and aims to please her affectionately, unlike Lee to whom she has been married for two years. Her feelings toward Diane become stronger that night when she enters her dim-lit bedroom, feeling the pleasure men envy, and accepting a kiss on the lips.

The Velvet Vampire was a transgressive film that introduced shocking content that was meticulously unfolding into horror cinema and the movie industry. Although its independent production got lost among the major horror film releases in 1971, The Velvet Vampire became a cult classic as a result of its progressive plot and dynamic female roles. The intimacy existent among women, and the free love movement, were both represented in the film without consequences and judgment in the plot. Susan and Diane shared mutual recognition and honor for their form of thinking, reacting, and their body’s anatomy. Their sexuality did not threaten them or victimize them, and instead it strengthened them. They were aware of their independence, their recognition of seeking pleasure and receiving pleasure by seducing men without having to give something in return. They were there for each other when troubles arose. This woman-to-woman bond was far stronger than the relationship between spouses Susan and Lee. In The Velvet Vampire, men are the diminished gender, the outcasts, prey to a story dominated by women much more powerful than they could ever be.