Some monsters exist purely in the imagination, while others are born of real life. Cults are among the latter; a type of horror reality, the spectacle of which can feel impossible to turn away from.

I was fourteen the first time I read Helter Skelter. It took two attempts. The initial description of the murders scared me so bad that I hid the book in a hall closet for weeks (as though the object itself would come alive and creepy crawl around my room in the night). But when I eventually devoured it, my interest was fueled by the same horrified awe that continues to make Charles Manson and his family subjects of interest (and relevance) to American culture in general. How could an individual armed with nothing more than racism and a poorly constructed conspiracy theory convince people to commit brutal murders on his behalf?

Like pretty much everyone, I’ve spent a fair amount of time the last few years thinking and talking with friends about cults and conspiracy theories; brainwashing and influence; the factors and qualities that imbue an individual with “social power” and the feedback loop between individual and collective (subject and spectator) that reifies it. What is the difference between the subject of a conspiracy theory and the monster in a horror story? What distinguishes a cult from religion, political affiliation, or general nationalism?

The answer- as I think many of us are acutely aware- is very little. It is the fact of this overlap that makes cults so very terrifying. Like any organized body, they are hungry entities; recruitment and indoctrination acting simultaneously as social contagion, consumptive incorporation, and ritual sacrifice. Because they exploit the deeply human desire for community and belonging, it’s no wonder the most famous cults have been organized around religious and political beliefs (Scientology, QAnon, The People’s Temple, Church of LDS) as well as actual corporations (NXIVM, LuLaRoe).

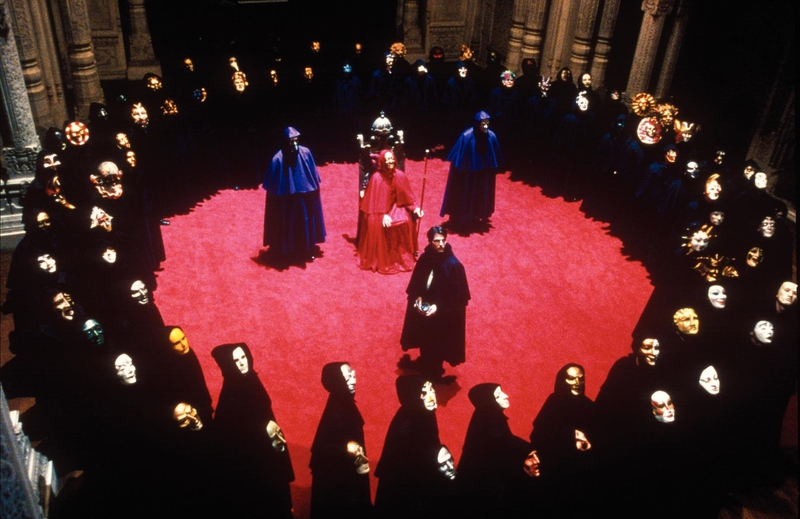

This tendency is reflected in pretty much all horror storytelling about cults, though sometimes with layers of irony. Rosemary’s Baby, Children of the Corn, The Omen, The Wicker Man, The House of the Devil, and Hereditary all illustrate the anxieties associated with satanic panic, where pagans, witches, practitioners of devil worship and blood sacrifice threaten to corrupt (read: consume) the children (read: the future); tropes that are satirized in projects like Jennifer’s Body and Satanic Panic. Other approaches take the sometimes symbolic, sometimes actual cannibalism of in-group formation and make that their focus. Mandy, Fresh, and perhaps most significantly, Yellowjackets, all demonstrate how ritual bonding occurs by ritually devouring the Other, while films like Eyes Wide Shut, Ready Or Not, and Society locate these same relational dynamics amongst the so-called respectable elite.

The argument can and is often made that any dogmatic in-group system that weaponizes fear ultimately functions as a cult, though members rarely perceive themselves, the behavior of those around them, or the situation as such. It goes without saying that cult and conspiracy theory are pejorative adjectives that function to discredit a given faith or ideological system while simultaneously naturalizing another. They’re boogeyman terms; rhetorics of monstrosity that can be wielded to either critique or nourish power, though they often accomplish both. Dianca London explores these nuances in her 2018 essay, “What Happens When You Mistake A Monster For a Friend” about the infamous Jonestown massacre, its under-discussed intersections with Black liberation struggle, and the danger of an “inability to discern the true motives that often lurk beneath the warm and fuzzy promise of solidarity and coalition.”

It’s the psychic, financial, and geographic control with which they’re associated that makes cults such potent renditions of The Swallowing. How does this show up in Society and The Sacrament?

Society

Part of what makes cults so dangerous is the sheer effectiveness of gaslighting as a method of manipulation. The organizing cause provides cover for those motivated by self-indulgence, which makes such behavior difficult to identify from inside, even if obvious to those outside. While such gaslighting is a hallmark of gothic horror, Brian Yuzna’s 1989 satirical masterpiece, Society subverts convention by trading the standard gothic heroine for a gothic hero in Billy (Billy Warlock), the son of a wealthy and influential Beverly Hills family, and trading the haunted, decaying manor for a lavish, well-tended mansion.

I’ve written before about hungry homes, how doorways function as the figurative and literal mouth of a house which is precisely where we meet Billy in the throes of a nightmare. As he anxiously creeps around his family’s mansion, he seems to be simultaneously searching and hiding from something unknown to both himself and the audience. In a therapy session shortly thereafter, he confesses to being afraid of people- his parents, his sister, Jenny (Patrice Jennings), and even the very therapist to whom he speaks- because he has the distinct, gnawing feeling that he’s different from them. He lives in the house and is part of the family but can’t shake the sense that he somehow isn’t; that there’s “something terrible underneath.”

His anxieties are confirmed following Jenny’s “coming out,” an event that might spur impressions of debutante balls and old episodes of Gossip Girl but turns out to be something far different. After a classmate (and Jenny’s ex) confesses to Billy he’s “bugged” her earring and the family car, the recording reveals confessions of incest and ritual orgies amongst the well-to-do of society. Every effort Billy makes to uncover the truth reveals nothing but suggestions of madness until his inevitable- again, trademark- forced hospitalization convinces his best friend, Milo (Evan Richards), that something strange is absolutely going on behind closed doors.

Throughout the film, his parents and therapist repeatedly stress that Billy will “make such a great contribution to society,” an innocuous phrase with sinister implications. Eventually, we learn Billy was adopted and raised to be a sacrificial offering to the cannibalistic cabal that makes up “Society.” In this film, the rich literally feed on the poor, whose “contribution to society” translates roughly to being consumed by society. The project clearly points to the cannibalistic nature of capitalism while raising valuable questions about how deeply we invest in artificial social hierarchies, the politics of which dictate so much of daily life. Beyond this, however, is its utterly unique portrayal of a cult as The Swallowing.

Satanic orgies have long been a feature of the sensationalism around cults in the public imagination, but Society charters new territory on this front, demonstrating enmeshment to the ultimate degree. In their true forms, Society members melt and meld together, mouths licking, sucking, bodies contorting, oozing into one another. Collectively, they sacrifice and then consume their victims through a ritual called “shunting,” the details of which I’ll abstain from describing (IFYKYK). The scenes are absurd and gross and horny and hilarious and somewhat awe-inspiring, as truth always is. But the real horror, of course, is that you can escape the house, but you can’t escape society.

The Sacrament

2013’s The Sacrament was Ti West’s last horror feature before the hiatus from filmmaking that preceded X. Released in an awkward period a bit too late and thus, ahead of its time in terms of cultural relevance (which Midsommar would eventually capitalize on), the film was shot in the found footage style; not just postmodern in the sense of presenting a “film within a film” but because it seeks to trouble the lines between fiction and reality, much in the way cults themselves do. The result is an exploitation-style project (and I do mean exploitation by all its definitions) that doesn’t offer commentary so much as demonstrate the complex, horrifying interactions between faith, power, spectatorship, sacrifice, and cannibalism.

It strikes me as inaccurate to say West was influenced or inspired by Jonestown. The film is essentially a fictionalized reproduction of its events, hereby constructing a kind of parallel universe where “the Eden Parish massacre” stands in as a double; the doppelgänger of an event, not just a person. In this universe, two Vice dudebros, Sam (AJ Bowen) and Jake (Joe Swanberg), accompany their friend, Patrick (Kentucker Audley), to visit his sister on a remote commune in an unspecified country, hoping to document the community for the website.

What they find is an organization whose ideology is constructed around a combination of Christianity, leftist politics, anti-technological sentiment, and what we’d probably now refer to as a desire for “the cottagecore lifestyle.” But as London notes, the congregants and victims at Jonestown were predominantly Black, and though West reflects these demographics in the film, its perspective is limited by its structure. If you already know that hope for a better future through collective action are bedrocks of Black liberation, then you may already understand what made Jonestown attractive to Black congregants. If you don’t, you won’t necessarily get that nuance from the Vice bros’ privileged perspective (being that their cameras, their gaze, their narration is the literal lens through which audiences experience the film, the film within the film, and community members, the subjects of the film within the film).

When we finally meet “Father,” it’s in the context of an interview which is, to me, the most terrifying part of the film. West wrote the shit out of this character, and Gene Jones gives a positively hair-raising performance of what is also essentially a performance. Sitting together on a stage before the entire congregation- Father’s chair next to a cross (therefore equating him with Christ)- Sam asks questions, and Father sort of answers, but mostly addresses the parish with knowingly impassioned diatribes about the sickness of American society. And here’s the thing that makes it terrifying—he’s not wrong. His critique is spot on. It’s also completely irrelevant in the face of his methods.

The problem with trying to build utopia- with investing in the notion utopia could even exist- is that it necessitates fascism; necessitates human sacrifice; necessitates a willingness toward monstrosity. The title of the film, The Sacrament, of course refers to the Christian faith practices, and one in particular: the ritualized symbolic consumption of Christ’s blood and flesh, otherwise known as the Eucharist or “taking communion.” An act of symbolic cannibalism, it is among the most significant rites in the vast majority of Christian denominations and locates divinity in the very act of consumption. That being said, communion can be taken through many practices, including that of tithing, which is essentially a financial demonstration of faith.

As shown in the film, people sold all their worldly possessions and handed that capital to Jim Jones as a material demonstration of their faith in his capacity to bring utopia to fruition. This is, at one point or another, what all cults demand: a total divestment from anything outside the organization and total investment in the mission. This is a type of incorporation; a type of devouring, first of one’s time, energy, social and familial life, financials, and, in extreme cases, one’s freedom and literal life. The Sacrament is so-titled because Father commands the congregation to offer themselves, their lives, as sacrament to him. Which is to say, he devours every delectable part of them, and when nothing is left, he feeds them poison.

There’s a great deal of fetishization that happens around cult leaders, but it’s their generals and fans- the people most invested- that imbue them with power, while fear of retaliation (often doled out by the same individuals) maintains it. Cults are The Swallowing shrouded under the guise of community. As London says, “we must learn to spot a wolf before it bares its teeth.”