Uglycute creatures who delight in chaos and mischief, gremlins are a relatively recent addition to the archive of human-imagined monsters. Though the word gremlin derives from the Old English, gremian, meaning “to vex,” they emerged as a variation of the goblin in British folklore, incorporated into myths and tall tales told by British pilots and other aircraft operators during the early twentieth century coinciding with the World Wars. The gremlins of these myths were devious imps disruptive to operations, conjured to explain technical malfunctions—as well as mental ones. Like all monstrous figures, they’re coded reflections of their creators’ anxieties, and the term was frequently deployed to scapegoat low-ranking officers and deflect accountability amongst high-ranking ones.

A member of the Royal Air Force, Roald Dahl is credited with first popularizing the monsters as the subject of his first children’s book, The Gremlins, published in 1943. Later, they inspired the famous episode of The Twilight Zone, “Nightmare At 20,000 Feet,” and its progeny in The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror segment, “Terror At 5 ½ Feet,” in which a gremlin appears on an airplane’s wing and school bus, respectively, and proceeds to tear the thing apart. Meanwhile, a single onlooker (Robert Wilson, Bart) watches helplessly, accused of madness when trying to alert those around to the imminent danger. As is often the case in horror, the question of the real or imagined is left suspended in the air; as much a matter of speculation as the mental health of the aircraft operators who first conjured them to explain the symptoms of combat-related trauma.

Amidst a sea of Santa slashers and Krampus revivals, Joe Dante’s 1984 classic, Gremlins remains the pinnacle of both Christmas horror, and the awkward subgenre of mythic creatures run amok (Demons, Ghoulies, Critters, Troll, Leprechaun, The Gingerdead Man, Elves).

While peddling his wares in a Chinatown shop, inventor Randall Peltzer (Hoyt Axton) comes across a singing creature called a mogwai (Cantonese for “devil”). Charmed by the preposterous cuteness, Randall is desperate to buy the creature as a Christmas gift for his son, Billy (Zach Galligan), and refuses to take no for an answer. The owner’s grandson defies his grandfather and makes the sale because they need the money, but also makes it clear there are three rules to care for the mogwai: keep them out of the light, away from water, and never feed them after midnight.

Of course, these rules are broken almost immediately. The revelation that water multiplies the mogwai and the market potential of such a discovery distracts well-meaning Billy and co. from recognizing that however adorable Gizmo may be, his progeny are absent the same sweet nature. The intentional malice in their mischief is shielded by a veil of cuteness that promptly evaporates when they eat after midnight and enter “the pupal stage,” transforming from fuzzy mogwai to scaly, red-eyed gremlins motivated primarily by the jouissance of destruction.

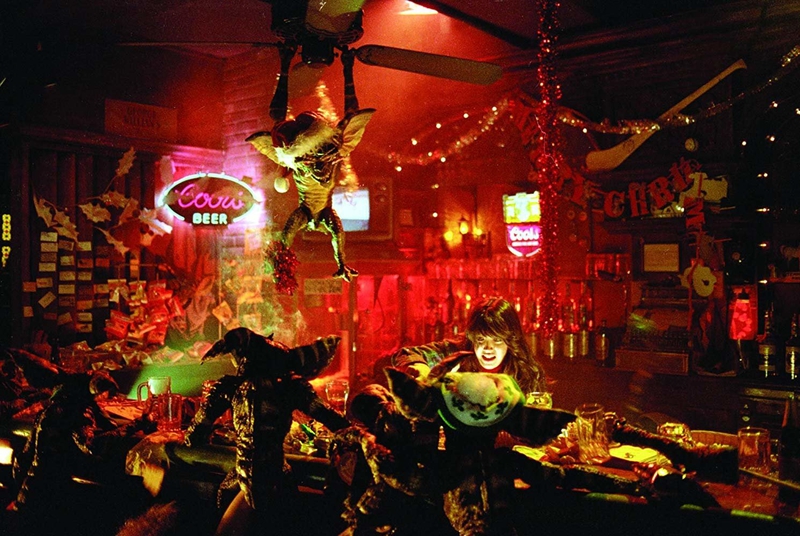

To this point, Gremlins takes something of an Itchy & Scratchy approach to gateway horror. Much of the film is made up of the artful chaos that defines gremlins as monstrous figures: Barney the dog strung up in Christmas lights, the positively deranged kitchen scene with Billy’s mom, the bubbling cauldron of the YMCA pool when Stripe submerges himself and unleashes the gremlin horde, the tavern, the movie theater, the carolers. But what makes them an iteration of The Swallowing?

For one, they operate as a type of swarm, overwhelming and laying waste to the sanctity of small-town America (on Christmas Eve, at that). And second, they are ravenous in their appetites. Though the gremlins don’t seem to harbor a particular hunger for human flesh, they don’t necessarily say no to it because, really, they hunger for everything. The state of being hungry is a destination in and of itself, and driven by manic consumptive rage, they destroy and devour everything in their path with absolute joy and good humor.

What is likely the most popular interpretation of the film is its critique of capitalist overconsumption. For all the comparisons between Kingston Falls and a Norman Rockwell creation, Gremlins is really playing in the tension between the prescriptive quaintness of small-town America and the gothic nature of its existence, amplified within the context of Christmas. Economic, spiritual, and communal precarity are very much so central considerations in this film, demonstrated by the initial sale of the mogwai, the mother who begs wealthy cat lady, Mrs. Deagle (Polly Holliday) for a couple weeks longer to pay back her loan (which Deagle denies), Billy’s father’s oafish commitment to invention which necessitates Billy be financially responsible for the family, not to mention Kate’s (Phoebe Cates) incredibly grim story about her own father’s death.

With Yuletide Gothic on max, the gremlins themselves can be read a number of different ways. Overt reference is paid to the monsters’ mythic origins in Mr. Futterman’s (Dick Miller) constant grumblings about the perceived ineffectiveness of foreign manufacturing, a movement that reveals the nationalism and xenophobia of attitudes about labor held by older generations during the time period. In this usage, the gremlins become coded representations of the Foreigner within the xenophobic imagination. Of course, he also primarily criticizes Volkswagen, and considering the company’s origins as a Nazi corporation, this could also be read to equate the gremlins with Nazis who walked free.

A more common contemporary interpretation is that the gremlins act and behave like hopped-up holiday shoppers, and if you’ve ever worked retail or food service, I know you know this to be true. Like sports and finance, shopping is an activity which capitalism actively encourages us to sublimate our most feral urges through. When you’re the worker in that dynamic- underpaid, understaffed, overworked, overstretched, forced to listen to the same twenty songs on repeat for half your waking hours- customers themselves become the gremlins whose hijinks are mucking up the works.

I’m also partial to Alex Hall’s reading of Gremlins as queer horror, where the creatures are as disruptive to the gender binary as they are to the general peace and well-being of Kingston Falls’ residents. To this point, Hall addresses their gender fluidity first in terms of the mogwai’s capacity for asexual reproduction, in which Gizmo becomes “the holy mother Mary figure of origin to all of the monstrous spawn thereafter; a cheeky nod to the baby Jesus’ own creation story…[and] a notable example of the queer immaculate conception in its most unabashed yet family-friendly incarnation.” Using Susan Sontag’s Notes On Camp, Hall goes on to delve into the gremlins’ ongoing treatment of “gender as performance,” where “the artifice and excess of the gender binary becomes palpable through their exaggerated masquerade.”

From the gremlin flashing their lack of genitalia to the Flashdance sequence, and the kitsch explosion that is the general set and puppet design, Hall is spot on in her estimation of “the artifice and excess” on display in this film. In this way, the gremlins aren’t just a swarm of devious imaginary monsters, but coded manifestations of a simultaneously imagined queer menace and a celebration of queer revelry. Keep in mind, the chaos portrayed in the film is joyous. Monsters they may be, but the antics- in all their hedonism- are fucking hilarious.

The gremlin mythos refers to havoc in machinery, the disruption of process and order. That’s what queer liberation is under patriarchy, no matter the morals or lack thereof. The monster exists solely as the object of a gaze, a projection, phantasmagoria. Gremlins is a reminder that there is pleasure in being the monster in revolt—and power in being the thing that devours.