Werewolves are quite literally ancient monsters. From The Epic of Gilgamesh to Ovid's Metamorphoses to the mythologies of several indigenous tribes including, yes, the Quileute (to whom Stephanie Meyer owes an incredible debt), but also notably the Navajo and Pawnee, storytelling about humans transforming into or taking on the qualities of wolves is almost as old as history itself–though not necessarily as we conceive of them today. Whether werewolf or shapeshifter, their renderings are reflective of the specific cultures that birth them. The Pawnee Nation reveres wolves for their resourcefulness as hunters and collective strength as pack animals (another unit of family), whereas the ideological symbolism of European Christianity renders them evil for precisely these same qualities. The one consistent estimation across time, continent, and culture is that wolves are tricksters: hyper-intelligent, skillful, and therefore unpredictable. As such, the monstrousness of werewolves is predicated on an unstable humanity whose physiology is outside their control and whose transformation gives way to inhuman appetites.

Before the invention of cinema, nineteenth-century literature overwhelmingly depicted wolves as synchronous with ecological and Native monstrosity. In She-Wolf: A Cultural History of Female Werewolves, Shannon Scott examines the "female werewolf as monstrous other" in the context of Honore Beaugrand's influential 1898 short story, "The Werewolves." She locates the source of this pulse in the seventeenth century colonial period and describes how during this time "the parallel between…Northeastern tribes and wolves came to represent the colonists' fight for survival in the wilderness of a new 'untamed' country," a narrative consecrated into at least one 1638 Massachusetts law: "Whoever shall shoot off a gun on any unnecessary occasion, or at any game except an Indian or a wolf, shall forfeit five shillings for every shot" (how this interacts with gun control is another essay entirely). A centuries' worth of white settler storytelling called indigenous humanity into question, suggesting they "like wolves, were a threat that must be eradicated," a movement which in turn "justified nineteenth century efforts to dispossess Indigenous people from their land" and provided a "method of rewriting history" by portraying them "as purely predatory."

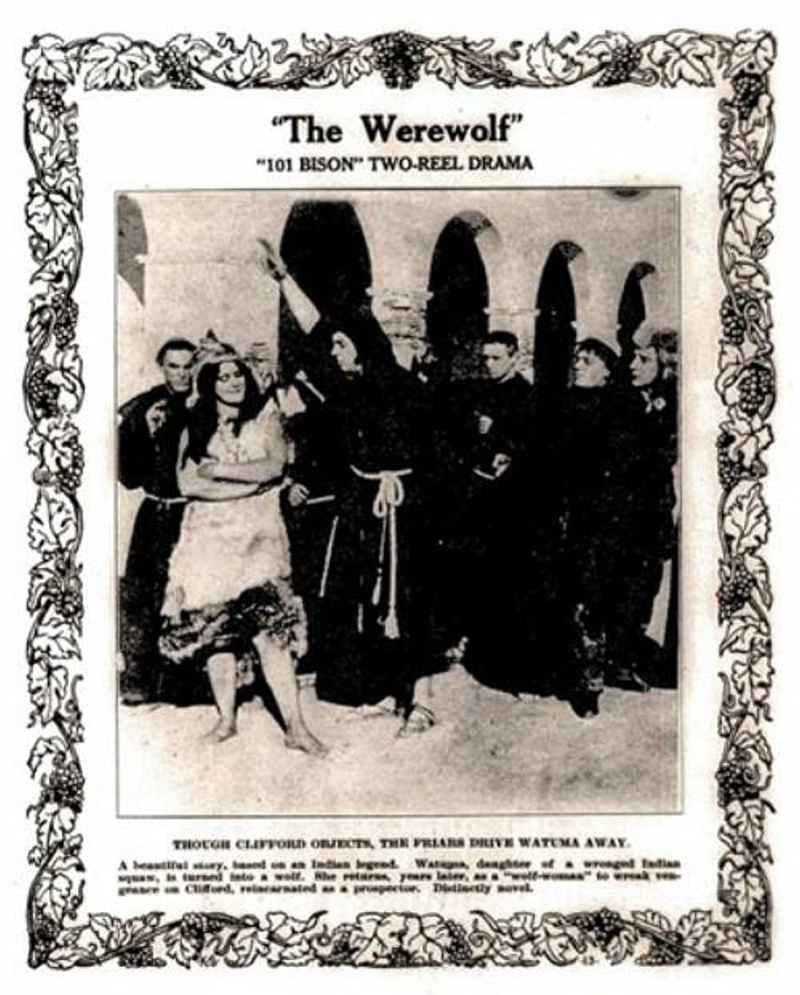

Beaugrand's short story would inspire the very first werewolf movie, 1913's The Werewolf. Though lost to a fire at Universal Studios in 1924, the film is purported to be about a Navajo woman with the capacity to transform into a wolf, who does so to seek vengeance against a group of white settlers that includes the reincarnated spirit of a man who murdered her partner generations earlier. While I'm inclined to say this sounds amazing, I can only imagine its treatment, especially when we consider this project was released a mere two years before The Birth of a Nation and represents the extension of this same centuries-old project; the monster working again as social-cultural technology.

While this propensity continued to be demonstrated in the earliest twentieth-century horror films- many of which are also lost, like The White Wolf (1914) and Le Loup Garous (1923)- the narrative began to shift with 1935's Werewolf of London. Here, lycanthropy is represented as a curse (in a call back to Metamorphoses), infection, and affliction tragically cast upon the wealthy, white scientist, Wilfred Glendon (Henry Hull) who is tormented by his transformation. Relevant is the curse's situation within Tibet, itself part of a long tradition of locating "evil" in the monstrous exotic as imagined by European literature (Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, for instance) and rendering this evil as a type of contaminate on/to the sanctified pure white body. Toward this point, we see how once centered within the body of the white male subject, the werewolf itself is transformed into a sympathetic monster.

From 1935 on, the overwhelming majority of American werewolf films derive from this narrative, though, as the century progresses, they come to be situated overtly around themes of troubled and toxic white masculinity. This is demonstrated in The Wolf Man (1941), I Was A Teenage Werewolf (1957), How To Make A Monster (1958), The Boy Who Cried Werewolf (1973), An American Werewolf in London (1981), The Howling (1981), Teen Wolf (1985), Wolf (1994), and An American Werewolf in Paris (1997). That said, what might we learn from closer examination of werewolf films that don't center this perspective? How does the pathology of the werewolf's transformation- and its appetite- shift accordingly?

The Beast Must Die

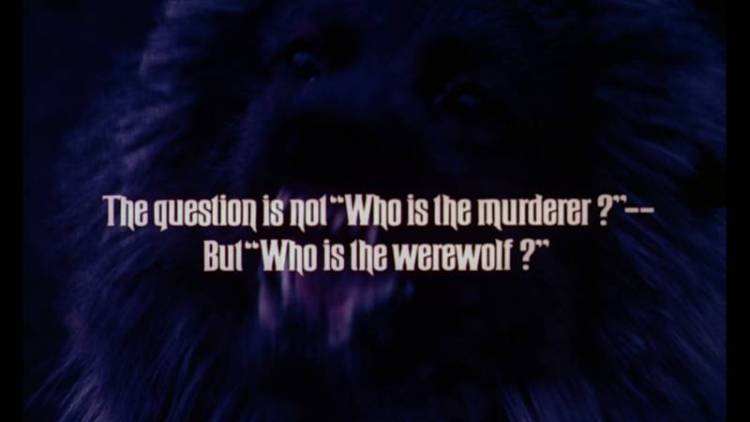

What can only be described as The Most Dangerous Game meets Clue with werewolves, 1974's The Beast Must Die takes classic gothic conventions and twists them in ways both compelling and utterly unique. The nineteenth-century gothic novel didn't just lay the foundation for modern horror, it also birthed the detective and mystery genres, predecessors of modern true crime. The Beast Must Die opens first by casting us, the viewer(s) in the role of detective, bestowing us with the task of sussing out who the werewolf might be amongst the cast of characters. Further, it introduces a thirty-second "werewolf break" toward the project's end that positively ruins its pacing but gives the viewer time to guess based on the evidence presented. Hokey? Undeniably. Nevertheless, it breaks the fourth wall in a fun and interesting way, primarily because the detective is almost always an audience stand-in in the first place.

The film's actual opening sequence is harrowing for the obvious history it evokes and how prescient that history remains. We follow a lone Black man as he is chased first by a circling helicopter, then through the woods by a team of militarized white men guided by an off-site controller who tracks his movements through live-action surveillance footage. The stakes feel incredibly high, but that tension gets muddied when he's caught…and nothing happens. After being caught and "released" three different times, he bursts out of the woods onto the clear-cut, manicured lawn of a mansion where a group of people sits casually around a table. Surrounded by armed guards, they fire upon him. We come to learn shortly thereafter that the bullets were blanks and the man, Tom Newcliffe (Calvin Lockhart), is actually an incredibly wealthy businessman with an intense passion for hunting. While it seems initially as though he was the hunted, in actuality he was testing the security around his massive estate, critical because it will "help [him] hunt the biggest game of all": the werewolf he's certain dwells amongst the six guests he's invited to join him and his wife, Caroline (Marlene Clark) that weekend, which just so happens to coincide with the full moon.

Lockhart's performance imbues the character with the quality of William Marshall's Blacula in the moments when we see him offended or enraged. Tom Newcliffe is worldly and sophisticated…but also a bit obsessed and over the film's course, increasingly manic. To Pavel (Anton Diffring), the controller, he describes how "in this world, you're either the hunter or the hunted…on safari or in the boardroom, it's all the same." He attests that "money buys things, men shape events," and later states to Caroline, the event he is most committed to shaping is the "dream of hunting and facing what no man has ever trapped before." When Caroline seeks to challenge him by asking, "what if the werewolf turns out to be me?" he responds with a single word: "pow."

The werewolf is, of course, representative of The Swallowing, but the werewolf is a monster born of pathologized transformation: a human lost to an inhuman form, abject for their transgression of boundaries. The so-called "guests" (more like subjects) he's assembled have all had histories of proximation to dead and mutilated bodies (one readily admits to partaking in cannibalism) but as his security is shaken and bodies begin to pile up, Tom's singularity of vision drives him to increasingly desperate- and increasingly ridiculous- behavior. At a critical moment, Caroline throws a candlestick through a mirror and exclaims, "I don't recognize you anymore. You have to win all the time…. You've let your passion for hunting turn into a bloodlust and I'll have no part of it." Raising a bloodied hand to his face, she tells him, "This is what you wanted." She's not wrong. Tom desired confrontation with a werewolf, and he found one–but in doing so, he's also forced into a confrontation with himself.

Tom's relentlessness and the degree to which he internalizes the self-prescribed identity of "hunter" is made all the more complex by Lockhart's casting. As with Duane Jones (Clark's Ganja and Hess costar) in Night of the Living Dead, it doesn't seem as though The Beast Must Die was written to have two Black leads, but their casting gives both the characters and the film extra dimension. How does the adoption and preservation of this identity interact with Black masculinity, particularly in the specific context of corporate America?

Ginger Snaps

The influence of John Fawcett and Karen Walton's Ginger Snaps is such that there's basically no way to talk about either werewolves or twenty-first-century horror in general without its mention. As we've seen, it's not that Ginger Snaps was the first to feature a feminine werewolf (The Werewolf, Daughter of Dr. Jekyll, An American Werewolf in Paris), or even the first to use lycanthropy as a metaphor for puberty (I Was A Teenage Werewolf, Teen Wolf), but it was the first to use the body of the monster as a means to explore experiences central to both girlhood and sisterhood. A decade before Diablo Cody wrote the words, Ginger Snaps was already demonstrating how "hell is a teenage girl."

Ginger (Katharine Isabelle) and Brigitte Fitzgerald (Emily Perkins) are prototypical weirdos of idyll suburbia; disruptions to uniformity for their obsession with death (which is really to say, escape) and their hunger to perform this disruption in ways that shock peers and adults alike. In the way of deeply enmeshed teen girls, they share everything- including a monolithic disdain for those around them- which serves to insulate and protect the world they create between and with each other. If being biological sisters wasn't enough, this dedication is consecrated in a secret blood pact- "out by sixteen or dead on the scene but together forever"- all of which changes the night Ginger gets her first period, is promptly attacked by a mysterious beast, and starts to become someone new; someone Brigitte, the younger of the sisters, can't quite recognize.

Fueled by its most overtly rendered subtext, the film's most dominant reading concerns puberty and "the curse" of menstruation. "I just got my period, okay. I've got weird hairs, so what?" Ginger exclaims when Brigitte raises concerns about her changing physiology. "That means I've got hormones and they may make me butt ugly but they do not make me a monster." Her denial is emphasized by mutually hilarious-if-mortifying scenes, one of assurance from the school nurse, set against their mother's ambivalence when she encounters- and proceeds to casually spot clean- some heavily bled upon panties while doing the laundry. The film takes PMS to a certain extreme ("the words' just' and 'cramps' do not belong in the same sentence"—big facts), but the project isn't limited to this singular interpretation.

There's also a definite reading where the horror of puberty isn't so rigidly gendered but rather illustrates the horror of gender dysphoria; of feeling completely out of control of one's meatsack. Relatively early in her transformation, Ginger begins to grow a tail. What starts as a small nub gradually gets longer and longer until the point where Brigitte has to help Ginger conceal it by strapping it down. In a later scene, Ginger- in the throes of grief and terror- attempts to cut it off with a knife until Brigitte stops her. Such body horror reflects experiences common for trans folks, the terror of which can be exacerbated by any number of factors. By its very nature (transformation, transmogrification), the werewolf is implicitly a trans monster.

It's also the antithesis of everything prescribed to cishet femininity. There's nothing dainty and delicate about being or becoming a werewolf. The process is violent, and the result is violence but rage, aggression, hypersexuality, and most of all, hunger, are all traits girls and women are stripped of in order to be perceived as girls and women under patriarchy. As Ginger states after losing control and killing someone, "No one ever thinks chicks do shit like this. Trust me, a girl can only be a slut, bitch, tease, or the virgin next door. We'll just coast on how the world works." That said, werewolves can also be enormously sympathetic, and we see this reflected in Brigitte's commitment to finding a cure, her attempts to protect others from Ginger, and to protect Ginger from herself.

Her love for her sister drives Brigitte to excuse a great deal, but this shifts the moment Ginger stops resisting her new form and embraces being "a goddamn force of nature." Her personal transformation is one rendering of The Swallowing; how its impact ripples out to her relationship with Brigitte, another. Ginger is so completely transformed- her past self swallowed by her present- that it's "almost as if [they're] not even related anymore." Despite her best efforts, Brigitte is unable to follow Ginger's lead; unable to bring herself to embrace these new appetites, and as a result, their "forever" is cut short. At one point, she tells Ginger, "You wrecked everything in my life that isn't about you. Now I am you." By which she means, a force of destruction. The freedom she desires ultimately only becomes possible by severing herself from her sister. That said, how does this rejection change when we consider Ginger as embodying a monstrously liberated form of femininity? Whose agenda does Brigitte's monstrosity ultimately serve?